I Got To Be Me

All About Style with GOS"

December 2025

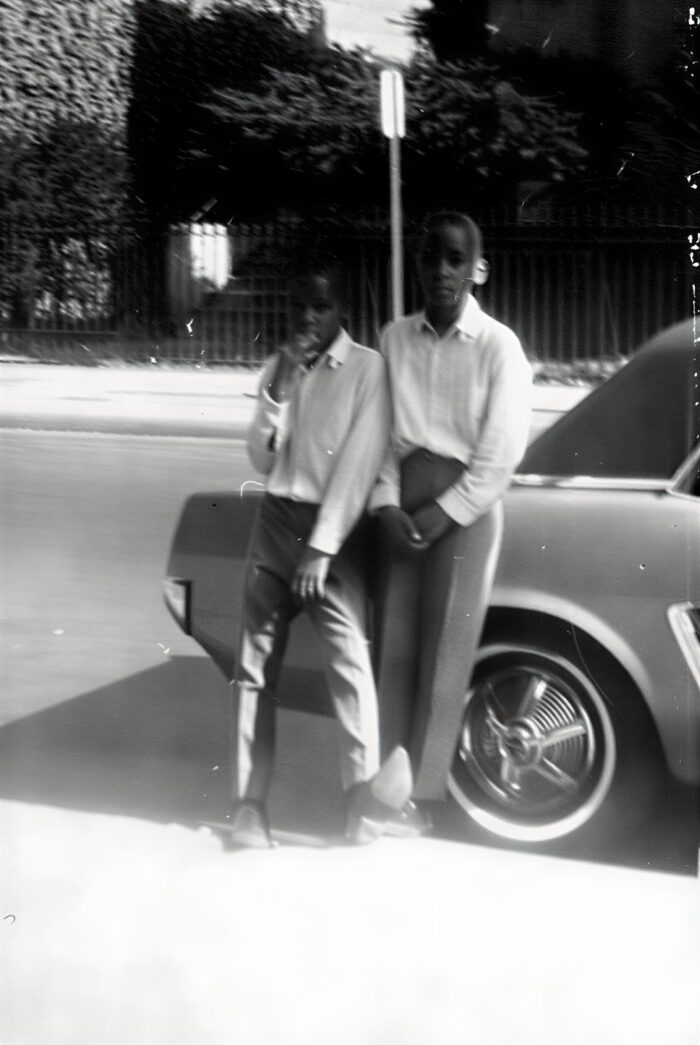

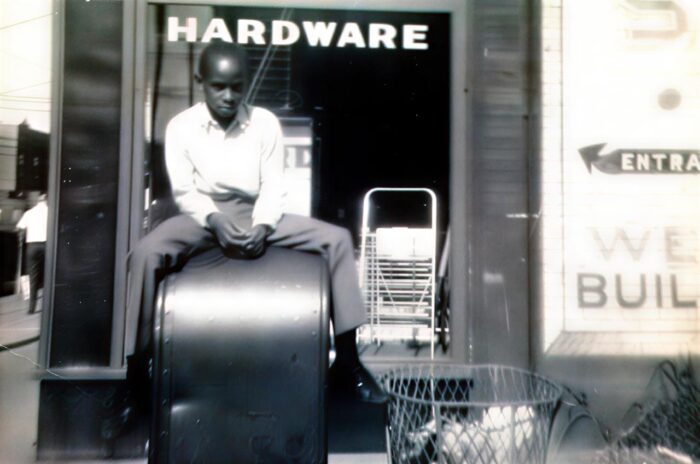

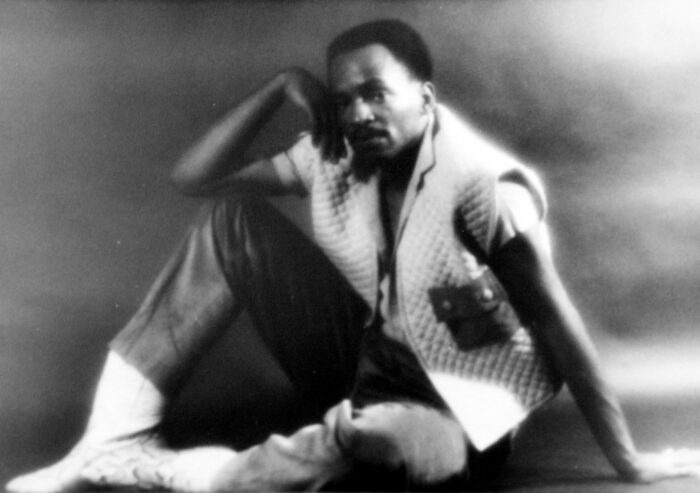

I was born in 1954 in Passaic, New Jersey, and lived there until 1982. My twin brother Jimmy and I were complete opposites. He was mechanical, while I was creative. He could build and assemble anything, and I could make it look beautiful. He blended in with the boys, but I felt no need to follow suit. Still, he was my closest friend and confidant. You couldn’t speak negatively about me around my brother because he would set you straight in a hurry. Unfortunately, he passed away at 40, which was a heavy blow for me, and it still weighs on me at times because I’m still a twin. I don’t say I’m a twin whose twin died; I say I’m a twin.

They used to call us Jimmy Jerry. Hey, Jimmy Jerry! He was shorter and lighter-skinned than I was, and there was no real reason to mix us up, except the assumption that twins are the same. And you know what’s wild? His full name is James Artis Simpson, but I became an artist. I’m Otis. So, Otis is an artist. I also had an older brother, Harrison, an older sister, Margie, and my baby sister, Frances.

New Jersey was a vibrant urban environment filled with music and culture back then. My parents danced in various ballrooms across the state and into New York. Newark was our entertainment hub, where venues like Symphony Hall and the RKO Theater hosted legends. Music always filled the air. Jimmy Smith, the famous jazz organist, often played at local clubs. If you passed one in the evening, you’d hear the organ wailing. This exposure built a strong connection to music and movement inside me.

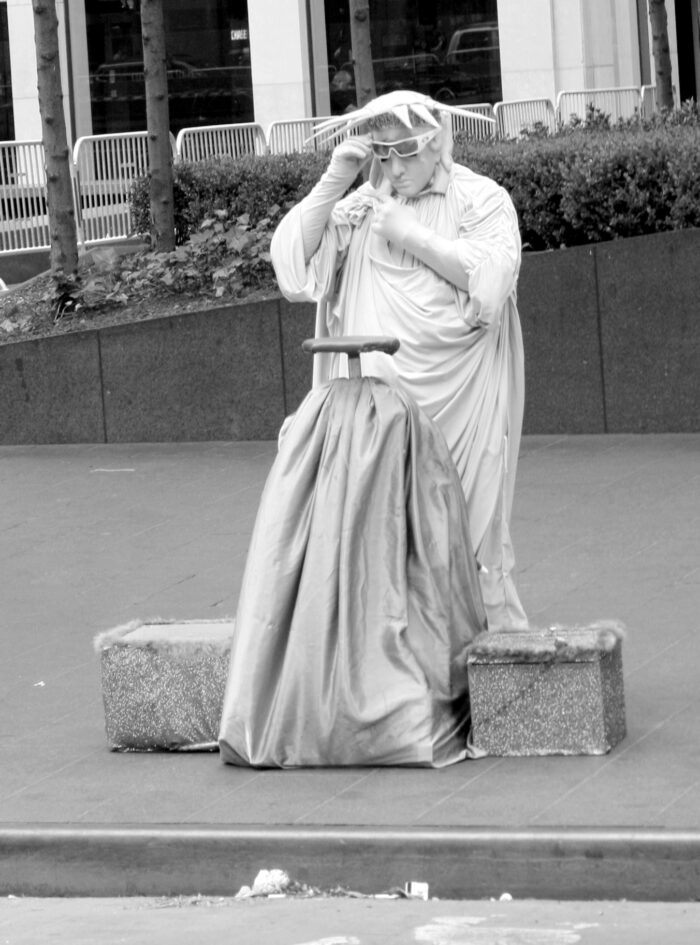

Growing up as twins, my brother and I were often asked if we could model for stores when shopping with our mom; we also participated in community and church events. Little did my mother realize that these experiences were shaping me toward my dreams. Just place me in front of an audience, and that’s all I need. When the lights are off, I’m nearly invisible, but when they come on, it’s like magic.

I may not have been the most creative member of my family, but I showed my talent. I was constantly filled with creative energy. Do you know what the Bissell carpet sweeper is, the one that stands up straight? That was my microphone. When I was young, my mom took me to see James Brown; that was all I needed.

I lost my mind when James Brown appeared at the Apollo. He flew in from one side of the stage in a brown suit, then left and came back in a white suit. I was bitten and smitten, and I had to find a way to do something similar. It didn’t have to be exactly what he was doing, but I knew something inside me would captivate an audience.

I was probably around seven or eight years old, in elementary school, in third or fourth grade. I had been going to the Apollo my whole life. Growing up, visiting the Apollo was something we did regularly. We didn’t wait for someone special to come; we went to see everyone. Every performance was special. The New York Daily included a movie section, and in the very corner at the bottom, there was always an ad for the Apollo Theater, announcing the upcoming performers. I would nag my mother to see everyone who showed up, whether it was blues, gospel, jazz, or anything else.

If you spent the night at my house as a kid, you had to be part of my singing group. I was always the lead singer, while my friends provided the background vocals. Occasionally, I would let someone else take the lead, but that was rare. James Brown’s “Live at the Apollo” was my show. I knew every beat. I would put a stocking cap on my head and style it in a pompadour. I knew when he went to his knees; I knew when he was sweating. There was a huge wall mirror in our dining room, where I used to perform. I was both the audience and the performer, and when I sensed he was sweating and about to go on his knees, I would run into the kitchen and put my head under the water faucet.

The Apollo is also where I first experienced fashion—if that makes sense. The entertainers’ attire amazed me. I hadn’t seen anything like that in stores. Where did it come from? What was it all about? At that time, my mother was especially interested in fashion. There were always fashion magazines around the house, and she also had a sewing machine, which I would mess with when she wasn’t home. I would gather scraps and try to sew them together to make outfits for my sister Frances’ Barbie dolls. One day, I accidentally sewed my finger, and that’s how my mother discovered who had been using the machine. From then on, she left the machine out for me and taught me how to use it.

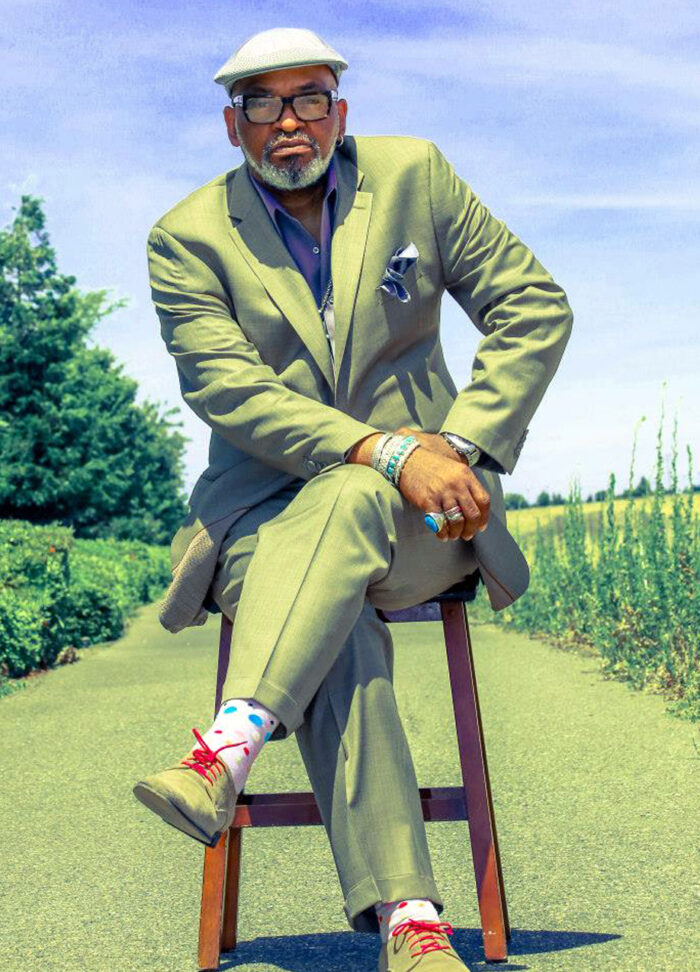

This was about me becoming myself. I lived on a street called Highland Avenue; at both corners of my block were apartment buildings, but everything in between was made up of houses. Near me was an apartment building, and on the first floor, there was a barbershop. When I left home, I’d stop at the barbershop and look at my reflection in the window. That was my last look at how I presented before turning the corner. If I thought it was too much, I’d go back into the house and adjust my look for the day, including what I was wearing.

One day, I went outside and saw the window had been boarded up. I could no longer see myself. That was the day I said, fuck it, you will take me as I am; this is who I am, whom I’m representing. And so that board, that window, and that Bissell carpet sweeper became tools of the trade.

Based on how I was dressed, people would ask me, “Are you performing today?” I would respond, “No, why?” and they’d reply, “Well, how you’re dressed.” I used to wear these outlandish clothes; what I wore back then would be a costume today! I wore them because I made them for the street. If people said, “Gerry, that’s a nice outfit,” I would go crazy and create a similar outfit for the stage for the guys I sang with. I served as a test dummy, and if people reacted positively, I knew they would go wild for it on stage. I’ve always considered myself an artist, but I never referred to myself as one until recently. I’ve always pursued art, with music as an extension of that. I probably started acting before I began making music. As a kid, I participated in school plays, including a performance in “The King and I” at Memorial #11 High School. I played the king’s sidekick and wore my first kimono in that show, which marked my first attempt at costume design. My mom brought home a green velvet kimono from work, lined in red, which I used in my costume. That experience sparked my love for kimonos. Now, I wear kimonos and believe it’s cool for men to wear them. When I went to fashion school, the first pattern I designed was for a kimono—long before Andre Leon Talley made them popular.

I became a fashion designer because I couldn’t afford the clothes I saw on other people. I realized that the best way for me to get something like that—something outrageous—was to make it myself. In my hometown, there was a fabric store called Dave’s Textiles. The first time I met Dave was through my sister, Frances. Frances could sew, and Dave’s Textiles was where she used to get her supplies. Dave was Italian, and he loved my family, so I have always maintained this “We are the world, we are the future, we are the children” attitude. I was never taught to hate anyone.

As I grew older, I realized that singing groups were emerging in Passaic. It’s also the hometown of the Shirelles, who went to high school with my sister Margie. Have you ever heard of Ruby and the Romantics? They had that hit song, “Our Day Will Come.” One night, I woke up to the sound of music at home, with people singing, “our day will come, and we’ll have everything.” I went downstairs to find a live performance by Ruby and the Romantics, who were hanging out in my living room with my sister Margie. Margie also dated James Brown. Do you remember the song “Give It Up, or Turn It Loose”? That’s his proposal to my sister, and let’s just say she turned him down.

Music has played a big role in my life. I mostly sang at home. Back then, I never let anyone see me sing in public because I was shy. Even though I now appear as this bold, outlandish-looking person, I do this for myself; it has nothing to do with others. You understand what I mean?

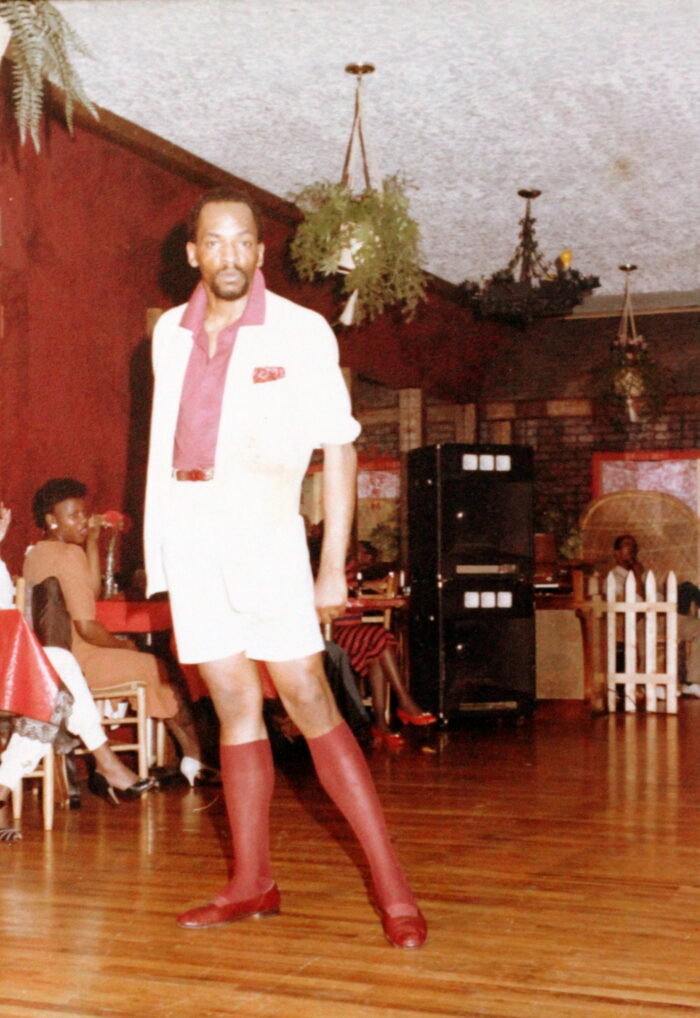

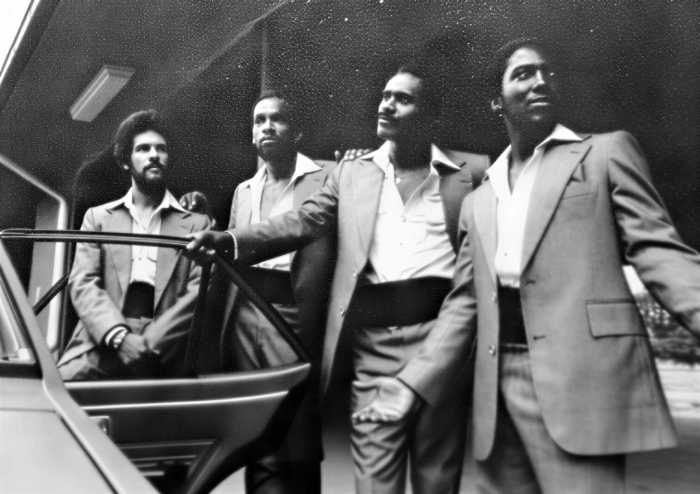

One day, I heard about a show featuring a band I recognized. There’s a group called Baby Bush, formerly known as Who, What, When, and Where, along with another singing group called The Friends of Finesse. I attended the show and felt annoyed because I believed I could do what they were doing, or even better. When The Friends of Finesse took the stage, I inexplicably booed them. The next week, I heard they were seeking replacements, but with the condition that they now wanted to wear uniforms or costumes. I decided to buy the uniform jacket from Hootch Boutique. I didn’t mind because I loved it—a blue blazer with a white collar and blue polka dots, with the sleeves rolled up. It paired well with white pants, a white turtleneck, and a blue velvet hat, completing the uniform.

I later found out they wanted me to buy the uniform, but someone else would be in the group. My stance was that I had purchased this uniform, so I should be part of the group. I made it clear that when I went on stage, I would be spotless. I told them I needed to create clothes for the group so we would all be on the same page. I continued to sing with them for eleven years. Part of the humanitarian award I’m receiving from my hometown is due to my involvement with Friends of Finesse, an incredible experience that was a highlight of my life.

If we were a group today, BTS, Backstreet Boys, and New Edition wouldn’t stand a chance against us. We were a 12-member group called the Friends of Finesse Orchestra. We toured from Canada to Georgia. The Friends of Finesse was also a vocal quartet. We were all capable lead singers, each with a unique sound, making us four groups in one. During rehearsals, each member would bring a new record or song for the group to sing. Then, we would learn each song and incorporate it into our show. Eventually, I was the only one consistently coming prepared with something new, so the show mainly featured my songs.

People also thought I was the lead singer because one night, as we were getting ready to go on stage, our percussionist, Harold McKinney, announced, “Ladies and gentlemen, Gerry Simpson and the Friends of Finesse.” Man, do you want to know how much chaos that caused? I never claimed to be the lead singer, he was just being a wise-ass. That’s just how he was. Nobody knew I had designed the clothes until it was over because I didn’t want to draw more attention to myself. I wanted everyone to understand that we were all in this together.

That was in 1972; I was a junior in high school when I joined the Friends of Finesse. I worked hard because, once again, if I’m a part of it, I want it to be the best. I’m going to do everything I can to make it so. For 11 years, that was my career. I still had a regular job, but I took on roles that offered flexibility. I’d ask my boss, “I’m going away for a gig this weekend. Can I have the time off? I’ll work double next week.”

It ended when we were all part of this play at the Village Gate in New York. The Friends of Finesse played the role of paupers in the play “EVERAFTER.” There was a scene where The Paupers stood up and sang a song. By the time that play reached New York, I was the Prince, and they were The Paupers. Right after that play premiered, I won enough money to pay for a trip to California.

Around this time, a friend named Gregory Grellin Johnson, living in San Jose kept urging me, “You need to come out here, come to California.” I kept insisting that I wouldn’t go to California unless someone paid my way because I couldn’t afford to save enough to make the move. He replied, “Who do you think you are? Nobody will pay your way to come.” I said, “Well, that’s the only way I will get there.”

This Model/Designer Competition took place shortly afterward. Instead of entering as a designer, I participated as a model showcasing my own designs. I won first place in the male models category and was prepared for the trip to Hollywood. As a designer, I needed to bring six or seven models for six or seven outfits, categorized in various ways. I fit into these categories—I’m a model and I design my own clothes—so I was effectively hitting two birds with one stone. Being a designer model, I also received credit for my clothes, which was part of why I won.

After I won the contest, my friend, who had told me nobody would pay my way, called to let me know that a woman he knew, Roda Grant, was hosting a fashion show in Redwood City, but her designer had quit. She wanted to see if I could come and create her clothes, and she said she would cover my travel expenses. That’s how I ended up in San Jose, California. Someone financed my trip, which was the most important part of the story.

Before settling in Northern California, I visited a friend in Los Angeles. When I arrived there I took a cab to meet her at his home on Sepulveda Boulevard. At that time, I didn’t know Sepulveda Boulevard was the longest street in America. I gave the cab driver the address; he dropped me off and left. It cost me every dime I had. So, I called my friend’s wife’s cousin, Vicki. She sent me the money to get back, and she’s been my wife for 42 years. I’ve been with her since I arrived in California, and she’s from my hometown!

It turns out she was my twin brother’s girlfriend when they were in elementary school. While I knew who she was, she only recognized me from a distance as a singer. Her name is Vicki Austin Simpson. Our wedding anniversary is on July 11th. My birthday is on July 18th, and her birthday is on July 25th. We have thirteen grandkids!

After the trip to LA, I stayed with people in San Jose until the fashion show was over. Then, I moved to Sunnyvale and saw a want ad for instructors at the Barbizon School of Modeling. When I lived in Jersey, I attended the Barbizon School of Modeling. After my second class, I received a letter from the school saying that there was nothing they could teach me. So, when I saw the ad, I applied, became an instructor, and eventually served as the head instructor for 11 years.

While I worked at Barbizon, I sang at Great America Theme Park from March until Labor Day. The only reason I auditioned for Great America was that one day I had my kids in the car, including my oldest. We passed a large marquee that said, ‘Great America’s auditions are coming for their singers.’ I thought we could go to Great America for free if I went there and passed the audition. That Sunday morning, my son woke me up. “Are you going to go for the audition?” I couldn’t say no because I wanted to teach him that one must follow through on what one says. So, I took my sons with me to the audition. There were hundreds of people there, and I ended up getting the gig!

I performed with a group called Summer Rhythms at Great America for two seasons. The stage show “Taking it to the Street” featured pop music. If we performed songs by Black artists, they had to be crossover material. Kool and the Gang. Safe stuff. I’ll never forget when I was on stage on Mother’s Day and said, “I want to say Happy Mother’s Day to all the mothers out there.” I was called into the office for using the word ‘mothers.” because they thought I was saying “mutherfuckers.”

I said Mother’s. M-O-T-H-E-R apostrophe S, not M-U-T-H-A. Do you understand what I’m saying? Singing at Great America, being one of the few Black talents in the band each season. I even had a white guy tell me he would teach me to sing like a black person. The crazy part is that he was serious!

I was thinking, what the hell is singing black? When I open my mouth, black comes out. I can’t help it. So, when I arrived in California, I couldn’t pursue music. Everyone wanted to know which school I attended and who I studied with. When I went to church and tried to sing, oh, you can’t sing in the choir with that earring in your ear. I took it out and asked, “What’s the difference?”

Once I started living in San Jose, I realized that fashion meant wearing socks in California. When I was working at Barbizon, my co-workers and I received an invitation to a new club opening downtown, which was expected to be a big deal for the city’s club scene. My coworker said, “Gerry, you’ve got to wear your best stuff.” I was looking for an excuse to go all out. People laughed at my outfit, and I spent the whole night sitting at a table in the corner. If I had been in New York City, or even New Jersey, I would have made a statement. But in California, they snickered, “Where the hell is he going?” I needed to find a way to create a look that stayed true to my roots. When I arrived, I had to dial it down. I embraced more T-shirts and a laid-back style.

When I arrived in California, I had $35. I had more dreams, hopes, nerves, and wishes than dollars. However, something felt off, as if it weren’t meant for me to be here, so I thought about moving back to New Jersey. My mom said, “Don’t come back here; if you don’t like it there, go somewhere else, but don’t come here!” At first, I felt offended because I was trying to figure out whether my mom had stopped loving me and if that was the reason she didn’t want me to come back. She was firm about it: I should go somewhere else if I didn’t like it. I later understood that she didn’t want me to return after leaving; she wanted me to be able to stand on my own.

Do you know what I discovered about myself after my mom died? I never really talked about it with her. I realized that my older brother served for many years, stationed in Germany, and he loved it; his life was great. But he came back home to New Jersey after getting out of the Army, being home is what messed him up. I guess that’s why she didn’t want me to come home—that once you leave, it’s hard to come back. It’s like a locked door, you know? It was about realizing that the place where my big brother grew up had changed, and when he came back, he found out that his friends were never really his friends. That’s how I understood my mom’s thoughts when she gave me that advice.

Nothing to Prove

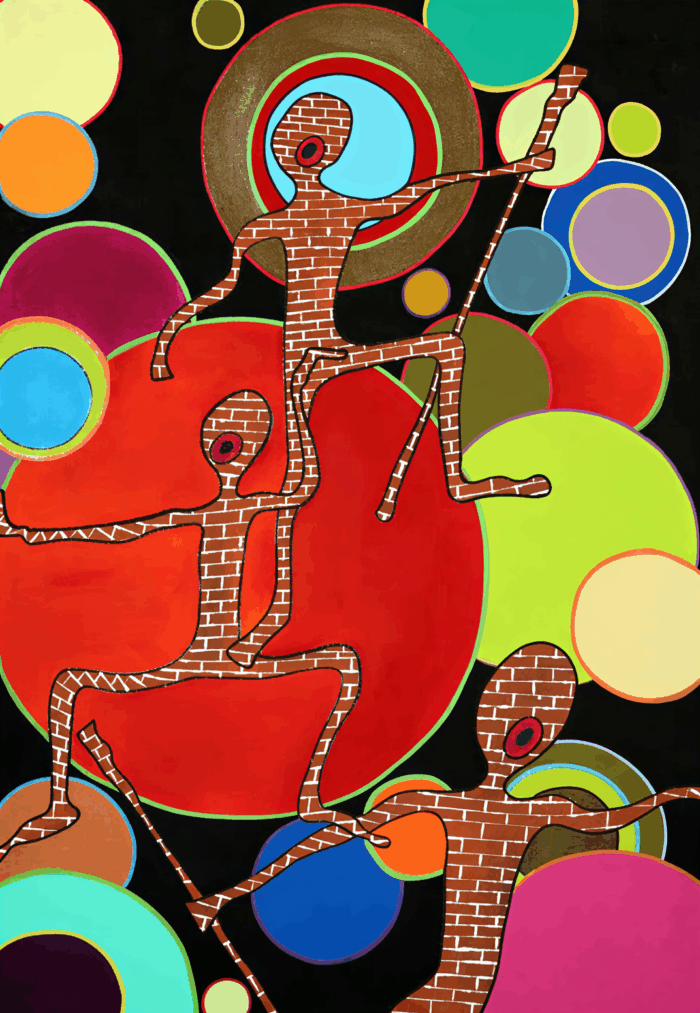

I started painting in San Jose, California. Once again, I couldn’t afford anyone else’s art, so I began channeling the energy of my children, which ultimately inspired an entire series featuring kids. I painted every night. I started showing up with my artwork, and people began to gravitate toward it. I haven’t been painting the round mouths and lips and such lately because my kids inspired those. My kids are grown and have their own children now.

When I arrived in Sacramento in 1999, I noticed art was everywhere. I came here wanting to share my art with others, but I didn’t find anyone who looked like me. I didn’t see a Black community of artists, and I knew very little about art beyond the idea that you go to an art show, drink wine, and eat cheese.

I aimed to learn how to display my artwork. I browsed through the Sacramento Bee, which had a small section dedicated to art galleries. That’s how I discovered the art galleries in Sacramento. Even without a guide, I didn’t let that discourage me from pursuing my passion. Instead, I had to carve my own path. I approached anyone willing to exhibit my art. If you want to showcase my work in your bathroom, let’s do it. If you have a wall big enough for my pieces, my first paintings measured six feet by 40 inches.

I wasn’t planning to go to the store and buy canvases just yet. I used what I had. My first ten years of painting were on recycled canvas from display backgrounds I used while working at Nordstrom. Okay. I consider my art funky—Greenwich Village funky, with that downtown, lower-end West Side vibe. I’d be in a loft on the West Side if I had a choice of places to be.

I’m a beatnik when it comes to my art. I was recently asked if I am a Black artist. Do I consider myself a Black artist? I said it depends on where I am. I’ve never walked around with that title. I’ve never said, “Hi, I’m GOS”. I’m a Black artist.” I just show up and I’m GOS”. But if you have eyes, you can see for yourself that I am a Black person who happens to be an artist.

I won’t waste time trying to prove who I am. You know that when I come to the door, I’m Black. Do you understand what I’m saying? It’s like going to a record store and seeing a sign for Black music but not for White music. Why does that have to be a thing? Why do I have to paint my community just so you can call me an artist? No, I will create what I feel. My feelings are abstract, and my emotions run deep. The first piece of art I made and hung on my family’s wall was an abstract scene. I didn’t start working with figurative art until I came to California, realizing that the people in my community needed to see something tangible. They needed to see trees if I said there were trees in the piece, or so it seemed.

But that wasn’t necessary for me. I chose to paint what I felt. It will be art. I didn’t attend school, so I have the freedom to do things you might not like. I know nothing about anything; I just do what feels right when I have my paint and brushes. There’s probably some music playing in the background.

I had no strict rules and didn’t stick to a specific neighborhood. I found artistic opportunities in the want ads at the back of the Sacramento Bee. I visited every gallery listed. If a gallerist was brave enough, they displayed my work; if not, I moved on. My experience as a model taught me valuable lessons, and one of those was to keep moving forward. When you face rejection, if someone turns you down today, it doesn’t define who you are. They might simply not be looking for what you offer right now. That’s the mindset I adopted for my art. If you decide not to exhibit my work today, it’s just because this style doesn’t match your exhibition or gallery. I learned that lesson quickly.

I started compiling a list of places to check out, and the first on my list was Kinks International, a holistic center focused on African American dreads and similar hairstyles. They had a dedicated art room. So, I went to Kinks for an interview and then visited the Art Foundry Gallery, a gallery owned by white people. I had met a Black woman who worked there, and she encouraged me to bring my portfolio with me.

However, on the day I visited, she wasn’t there. Instead, a woman named Gloria Burke was present and asked if I had my portfolio, which was a loose-leaf binder containing some snapshots of my art. I handed it to her, and she started flipping through it. She didn’t look at me, but she said, “I’m not interested in your Black issues, but I’ll take your abstract work.” I sat there in disbelief, holding back tears of anger because I couldn’t believe what I heard. I couldn’t figure out where my family had moved. I wondered if this was how things were done here or if Ms. Burke thought it was okay to speak to people in this manner. The pieces she considered to be “Black issues” were scenes of children playing. My kids are my inspiration. The images I draw of children highlight the positive aspects of Black life. Ironically, she commented that all the pictures of kids playing, going to church, and reading a book represented “Black issues” to her. I later found out that she’s married to a Black man.

After I found out, I was truly blown away; however, there was a lesson: while she could love a Black man, she didn’t have to like his people or love his community. I often wondered if he knew how she felt. Did he realize that she had approached other Black people the same way?

Ten years later, Gloria showed up at an exhibit I had at the Sojourner Truth Museum, and the first thing I did was ask to take a picture with her. In my mind, it was a ‘How You Like Me Now’ moment. You thought all you had to say was those things to me, and I’d go home and burn all my canvases and throw my brushes away—but, no, she ignited a fire within me that still burns brightly today, 25 years later.

I wasn’t that insecure. No, I went home and painted more. I didn’t get mad; I got even—there was no reason to get angry. From there, I kept painting and found more places to showcase my work.

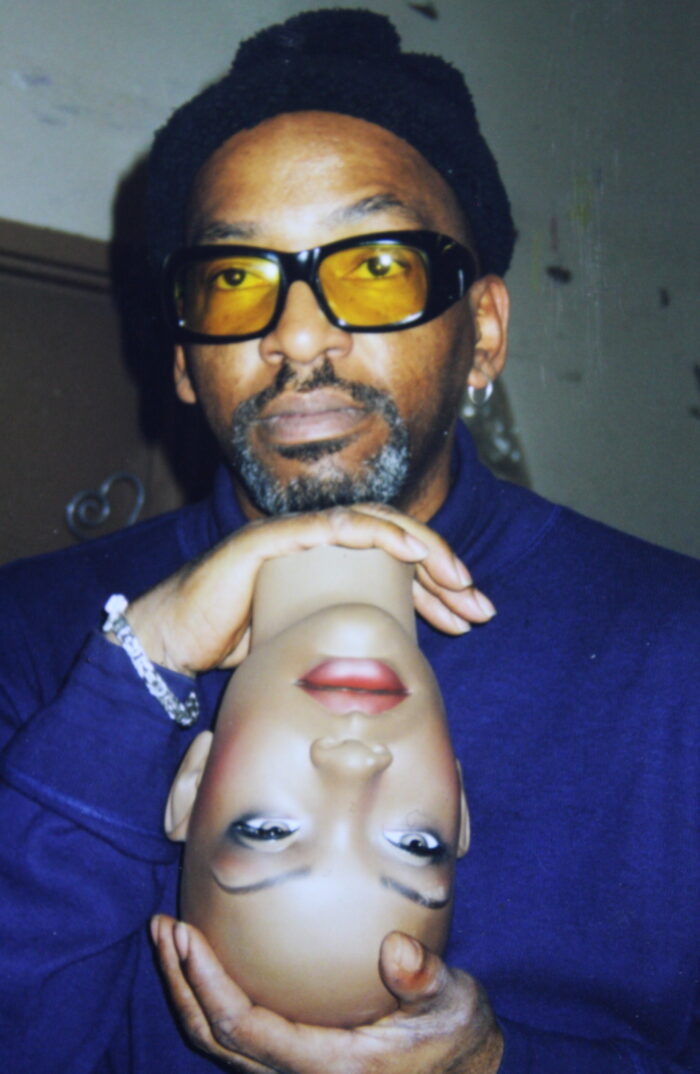

While at Kinks International, I met a woman getting her hair done who worked for KVIE, a local television station. After seeing my art, she mentioned me to a producer, as he was creating a segment on people who had found their passion in art. He came to interview me for the show. Before all this, I was introduced to a woman who was writing a book and needed an illustrator. I sent her samples of my artwork for consideration to illustrate her new book, but I never heard back.

So, now this guy wants me to be on this TV show, telling me I would be with two other people. Ironically, one of the guests is the author to whom I submitted my work for consideration. The other guest was the artist she selected as the illustrator. I didn’t get a chance to meet her then because we were interviewed separately, but years later, I finally had the opportunity to meet her. After I did the show, the same producer reached out to me to be one of the on-air guest artists for the KVIE Art Auction broadcast.

I’ve submitted art to KVIE auctions, but they have consistently rejected it. Now, I’m being asked to appear on air as one of their on-air talents. Okay. My job is to describe the beautiful art up for auction, so I’m there doing my thing. “Look at the texture, blah, blah, blah. I can almost fly that skyline.” That kind of thing, you know, to encourage people to buy.

Before I went in for the first segment, I was telling the producer, who happens to be a white guy, the Gloria Burke story. He laughed, and I said, “Wait a minute, this is serious, man. Why are you laughing?” He replied, “Are you ready to meet her again?” I asked, “What do you mean?” He said, “Well, she’s the director of the art auction.” I replied, “Yeah, I’d like to meet her.” So, I walked in there, and she acted like she didn’t know me. I pretended not to know her, and I hosted the show three years in a row.

During one of those shows, this guy was the main host; I was with him, going toe-to-toe, talking and everything, when he suddenly stopped mid-sentence, on-air, and dared to ask, “Why are you acting like you know what you’re doing up here?” I just kept going. He didn’t realize I owned a modeling and acting school, so the things I was doing were what I taught people. These are just a few strange interactions I’ve had in Sacramento that have been wild, but they haven’t made me mad. They motivated me to keep going.

When I first moved here, someone told me that my art would never sell and that I would never succeed because I wasn’t from here. Well, here’s the thing: I’m from America, which means I can call anywhere I want home, and, baby, Sacramento is part of America. I apologize if my authenticity helps you see who you are. People often ask why I only put a quotation mark on the right side of GOS”, and it’s about being told I wouldn’t succeed in the arts in Sacramento. It’s like saying: take that! Especially when someone tries to extinguish my light, it only makes me more determined to master this art. This is how I channel my anger, and I will do everything in my power to make my point clear.

Community

To me, community consists of those—whether family, friends, or like-minded individuals—with whom you engage to create change. These are the people with whom you share ideas and common goals.

I acknowledge that I am part of the Black community; however, I do not prefix everything I do with “Black.” As the song goes, “he’s got the whole world in his hands,” not just a piece. The entire world is part of my community. I wouldn’t be where I am without the help of others. When I talk about others, I mean different nationalities, people from various places, and those who are different from me. Yet, we are all people.

Community also means bringing people together. Yes, there are times when only members of the Black community are present, but there are also times when I visit other communities. I might be the only Black person there, but I can walk into any community without fear in my eyes. I do not clutch my beads. I do not clutch my purse. I simply relax and be.

As I mentioned, the children I paint come from diverse racial backgrounds. I also have a character named Otis. He’s the one in the red and white shirt. Otis’s friends are all human. I created a character who considers everyone his friend. So why wouldn’t I feel the same way? Because Otis is me—Gerald Otis Simpson. GOS”, my nom de plume, allows me to be THE artist without involving my government name in my art at showcases. I can be Gerry without any connection to my art.

The name GOS” comes from my time living in New Jersey. Many people in my hometown think I became GOS” after moving to California, but it started when I worked with youth on arts and crafts at the Youth Services Bureau. Whenever I painted something, I signed it with my initials; my boss, Dorsey Hayes, said, “I’m going to call you GOS” from now on.” So, I took GOS” with me to the West Coast. When I first started designing clothes, it was under the GOS” Designs East banner, showing that GOS” Designs had an East Coast flavor.

When I arrived in Sacramento in 1999, there was no fashion scene, so I put GOS” Designs East on hold. I only made clothes for myself when I wanted to go out, painting on clothing. I didn’t pursue fashion publicly again in a big way until 2017. Now, I’m not just creating clothes; I’m crafting sustainable fashion from used materials. So, who am I now? This is GOS” Art Wear. If you’re not hanging my art on your wall, hang it on your back. Again, as I mentioned, the entire GOS” Art concept allowed me to hide behind GOS” because I wasn’t sure what people thought of it. However, I had already decided that not everyone would appreciate my art and that I would focus on those who do.

I found a community that embraced my creativity because it was something unique and distinct. People supported my self-expression and provided spaces to showcase my work. Writers wrote about me, which helped spread the word about my contributions to the community.

Nan Mahon visited Oak Park and attended one of my shows. I didn’t know who she was; she came with someone and mentioned that she liked my art. At that time, I wasn’t aware that she was a writer for the Sacramento Bee. Eventually, she wrote two articles about me in the Bee and one for another publication. That’s community engagement on a large scale.

My family was one of the few Black families in my neighborhood. I now live in Elk Grove, where we are the only Black family on my street. I had to learn how to connect with others many years ago, not just within my community but with everyone in general. This understanding started in my childhood. I had a friend named Rusty who lived two houses down. Rusty’s dad was a police officer, and we used to play cops and robbers. Rusty wanted my twin brother and me to be the robbers. Go figure. But Rusty was our best friend. When I reached high school, Rusty stopped talking to us because he made new friends who were all white. Over the past three years, Rusty has reconnected with me on Facebook.

One day, I called him Rusty on his Facebook page. Another guy came on there to set me straight for calling him Rusty. He now goes by the name Ray. His father’s name was also Ray, so we called him Rusty. Rusty got on there and told him, “You can’t straighten him out because he knew me before you, and that’s what I was called back in the day.” Rusty’s dad always looked out for my brother and me, especially after he became chief of police; he took care of us.

Artistic Expression vs Commercial Success

I will always express myself creatively, regardless of financial constraints. Money doesn’t define my passion for my craft. That’s simply how it is. My creativity isn’t limited to what’s on this table or that wall. The way I carry myself and how I dress—those are parts of who I am every day. To achieve commercial success, you must stay in the game long enough to achieve it, but that still doesn’t guarantee success. You know what I’m saying? There are no guarantees.

You need to realize that, even though Sacramento is known as an art city, do people really buy a lot of art? I don’t know. We all aim for commercial success. While I’ve sold many of my pieces, I still have some left. I will always have backstock, and I will always have something new.

During the Harlem Renaissance, many artists weren’t considered prolific because they typically produced only one or two pieces. They didn’t have a substantial body of work, which is why I paint every day. When these eyes close for the last time, you’ll discover many things. My family will be surprised by many things when I’m gone.

My creative expression is evident in everything I do. It’s about showcasing myself first, long before thinking about making money. I always wanted a job designing displays and dressing windows. I had only seen one Black person involved in visual merchandising in my hometown. He worked in every big store there, but he wouldn’t take me under his wing.

I worked in the display department at Nordstrom, which gave me many new opportunities. I gained my education as a visual merchandiser through hands-on work, which helped my knowledge and understanding grow. Nordstrom was my university. The guys I sang with also contributed to my learning. They gave me chances to do choreography, costume design, and improve my people skills. During my time at Nordstrom, I worked behind the scenes, completing tasks before the store opened. I finished all my work by 10:00 a.m., like an elf working at night.

Nordstrom’s Christmas decorations were never unveiled until the day after Thanksgiving. I didn’t have Thanksgiving dinner with my family because, while they ate, I was sleeping. This was because on Thanksgiving Eve, I was busy assembling Nordstrom’s Christmas displays. For 12 years, I missed Thanksgiving with my family. Wow. That first year when Thanksgiving arrived, I felt lost because I didn’t know where I fit in.

So, yes, Nordstrom was a blessing, but it was also a curse; there was a lot of racism at Nordstrom. It didn’t come from the company itself; it came from the people they hired to run it, like district managers and others in similar roles. A white guy approached me and introduced himself as my new regional manager. He said, “dude, I just want to let you know that I’m not going to be afraid of getting in your face if you get out of line.” I looked at him, laughed, and walked away. I didn’t say a word; I just laughed. It’s like, who the fuck are you? The next time he came, he said, “You know, I would be remiss if I didn’t ask you this question: why aren’t you afraid of me?” I looked at him again, laughed, and walked away.

From that day on, he dedicated himself to firing me. He was eager to find any reason to let me go. In very fine, small print, they can fire you for being late on your credit card payment. Seriously. The morning I was fired, I had just paid my credit card bill, and the store manager attended my termination meeting. He walked out suddenly and said, “I’m not gonna be a part of this.” These are just a few of the hurdles I’ve had to clear to get a chance to show what I can do.

Teaching

One day, I got a call from the lady in charge of the Visual Merchandising curriculum at ARC, asking if she could bring her class to see the store. I told her, “Sure.” I wasn’t supposed to say that, but I did—and forgot about it until I got a call from the operator upstairs, saying, “Gerry, 35 people are waiting for you downstairs by the coffee shop.” I thought, what? I took them around the whole place. I showed the class everything, the whole nine yards, even how to take out the garbage. A year later, I received a phone call. Hi, this is Marie Cooley. “How would you like to teach at American River College?” I said, “Well, I’m going to be honest with you, I don’t have a degree in anything.” She replied, “Well, that’s not what I asked you. How would you like to teach at American River College?”

I said, “Great,” and went to the main office. I’m sitting in this room filling out the application. Other people have stacks of papers; they have degrees and everything. They’re stacking their degrees like skyscrapers, and I’m starting to wonder, why am I here? What am I doing here with these people?

Then I thought about it. She told me to come, so I filled out the paperwork and walked out the door, where a Black lady was waiting. I asked her, “So what’s next? Do they call you for an interview?” She looked at me and said, “Well, what makes you think you’re going to get an interview?” I replied, “I am sorry for being so confident. Have a good day.” And I walked away. A few days later, I received a call back, and the woman who had initially thought I wouldn’t get an interview was working again. I waited in line until I could get to her, and I said, “Hi. I’m here for my interview.”

She looked at me and said, “You’re not from here, are you?” I asked her what she meant, and she replied, “You’re really different.” I responded, “Thank you for noticing. So now, where’s my interview?” I worked there as long as I was employed at Nordstrom. It was a good experience, and I had a great time. I never thought I would become Professor Simpson.

I’ve worn many hats in my lifetime; however, becoming a college professor was not one I expected to wear.

Del Paso Blvd

I arrived in Sacramento in 1999. I wasn’t sure what I would do here in Sacramento when I first arrived; I didn’t know how to fit in. I didn’t understand my place. Here I am in Sacramento: this artist, this fashion designer kind of guy. I work at Nordstrom, you know. Very few Black people shopped at Nordstrom in Sacramento. At the time, people didn’t even realize I existed in that world. I had the chance to connect with many people at Nordstrom, and I want to thank Councilman Allen Warren sincerely. Are you familiar with him? He was the vice mayor while Kevin Johnson was the mayor. I was introduced to Allen Warren through his wife. I worked at Nordstrom, where his wife shopped, and that’s how I met her. It’s funny how connections happen — it’s like crocheting. I crocheted my way through town.

I scheduled a meeting with Allen Warren at City Hall, where he had a stunning art collection in his office. I wanted to discuss the possibility of displaying my work there. Unfortunately, on the day of our appointment, I was struck by a bad cold, and it was pouring rain, which made it impossible for me to go out, so I had to cancel. There used to be a seafood restaurant on Del Paso Boulevard that served Black cuisine, and I’ll share the name shortly. I was walking in while Allen Warren was coming out, and at that time, the restaurant was exhibiting my art throughout the place.

I greeted him and said, “Hey, how are you?” He replied, “Fine.” I then asked, “How did you enjoy your lunch?” He responded, “Very good.” I asked, “What did you think of the art?” He said, “Oh, I love it. It’s great.” I took the opportunity to tell him it was my work! He directed me to a specific address: 1825 Del Paso Boulevard, telling me to ring the bell outside, and someone would come down. However, when I arrived, the windows were covered with brown paper, and I couldn’t make the connection—I had no clue.

I knocked on the door and rang the bell. A woman answered and asked, “Are you Gerry?” I said, “Yes.” She told me, “Let me open the door for you.” I moved from the front to the back, taking in the space. He said I could have it if I liked it, and I used it for seven years. It’s because of him that I had the chance to open GOS” Art Gallery Studio. I never talked about it publicly because I think sharing who did what for me was a personal matter. It’s not that I wasn’t grateful, but I was unsure how that person would feel about me telling others, setting them up for hearing, ‘Oh, you did it for him.’ From others. So, for seven years, I kept it a secret. I lived on a boulevard and caused a little chaos as much as I could. In a good way, in a big way. I brought people to the Boulevard who would never have come otherwise. I remember the first time I put together a show with someone; someone told that person they shouldn’t perform with me because people get killed on the Boulevard.

The hottest spots in the city are often the most risky. In 2013, I thought of Del Paso as my version of Greenwich Village, my Soho. It felt like an uptown neighborhood, so I called it “Uptown in the Design District.”

I made the news and gained attention. It received plenty of publicity. When I opened the gallery, it was standing-room only. I had done something unique for Sacramento: I brought people from all over the city to one place. I had been in Sacramento for years, and all I heard was, “I don’t go to that side, and I stay over here, and I don’t go over there.”

I organized exhibitions for other artists, including a show for Sukee Kwon, a Korean artist who struggled to find another gallery to showcase her work. I was the underdog gallery, presenting artists who were told they couldn’t have a show elsewhere. It became a lesson for all artists because of the challenges involved. As a gallery owner, I knew my job was to provide a space for artists to display their work. I’m not asking for anything in return. I take a percentage of what you sell, but I don’t request anything else. So, I’m giving you everything. When I first arrived in Sacramento and learned about being an artist, it was simply about finding a wall to hang your work on.

This, however, posed challenges for fellow artists. They would come to my well-attended shows, but few would show up when it was their turn to exhibit. I thought, “Okay, wait a minute. You must understand that, as an artist, it’s essential to cultivate your audience. I’m providing you with the space; you’re expected to invite people, gather some friends, and announce that you’re having an art show; and thank you for attending my exhibit.”

I stopped showcasing others’ work, not because I wanted to, but because of the difficulties involved. I couldn’t guarantee an audience for them, just as they couldn’t ensure one for themselves, which made things tough. Eventually, a day came when standing on that cement floor became unbearable for me. I could no longer tolerate those floors. Spinal stenosis is a formidable opponent.

While it was open, it was one of the most precious gifts I received and could share with Sacramento. It was a place unlike any other. I held fashion photo shoots on the streets, and people cheered me on. They looked out for me. I accidentally left my door unlocked all night twice, and nothing ever happened. Once, a homeless person went to the bathroom in my doorway, and the other homeless people went off on her, “I know you’re not doing that to GOS”. Clean that up!”

I also offered various activities, including poetry for individuals aged 55 and older, along with The Straight Out Scribes, a mother/daughter poetry team . I hosted fashion shows on Del El Paso Boulevard. While the attendees at my studio might not have traveled along the Boulevard, that didn’t mean they were avoiding it. I attracted a diverse mix of people from all walks of life.

I hosted a show called “My Friends with a Little Help.” My artist friends Daphne Burges and Shonna McDaniels participated, along with many top Sacramento artists, allowing me to showcase everyone. There wasn’t a single artist I overlooked.

I organized photography exhibitions featuring Sacramento photographers and hosted a black-and-white display called “Del Paso”. I invited both professional and amateur photographers to submit their best black-and-white shots. In the center of the room, vintage antiques and wooden ladders showcasing old cameras filled the space with charm.

I also hosted the Sukee Kwon show, which highlighted the Lotus. She hand-painted my curtains and created live artwork during the events. Another notable show was Eric Jon Alfonso’s “Mannequin Madness,” in which he created captivating pieces using mannequins and resin. I have photos documenting all these experiences.

It was truly an amazing venue. People would walk in and share their appreciation, commenting on how much they enjoyed the atmosphere. I’ll never forget a homeless man who came in and gave me a bouquet made from wildflowers he had picked from the nearby streets. You could tell this man had worked as a florist at some point. That’s the kind of love and respect I received from the community.

People would come, sit, and talk while I sewed. That book—that’s about me—A Rage in Sacramento. Ebony London wrote that book. Every Thursday for a year, she came, sat, and talked to me. When she prepared for her first art show, she made sure I was there to present this book to me.

It’s amusing to think about. The first exhibition I did in Sacramento was held at a seafood restaurant called Off the Hook, which I mentioned earlier. It was a soul and seafood spot, and the owners of Off the Hook previously owned Gallery 1910, located at 1910 Q Street. I showcased my work there for nearly seven years.

Off the Hook contacted me to say they were closing. At that time, I was organizing my show for my exhibition space. When they called to announce their closure, they asked me to retrieve my art. The pieces displayed in the restaurant were moved right across the street, marking the start of my first exhibition.

Black and Forward

It felt like pulling teeth to get people to come. That neighborhood was one that nobody wanted to visit, you know? But I showed up and did my best.

The challenge wasn’t the space itself but the neighborhood. You had people sleeping on the sidewalk while gunfire erupted down the street. That was a challenge. You know, a guy owned the store across the street. Two young men entered his store to shoot him, and he drew his gun and shot them. One of them passed away right on the corner by my studio. These are the kinds of things I had to deal with. I left the studio one day, and about half an hour later, three people were shot on the other corner.

I could have faced robbery or even been shot for being in that location. However, I felt comfortable going there. I wasn’t afraid. It feels like being in a wild jungle. If the animals see you as cool, they will be cool with you, too. Yeah. Do you understand what I mean?

After an event, I approached a group of homeless individuals one day and said, “Hey, y’all, I have some leftover food. Come on!” I will never forget this moment. I had ordered too much Chinese food. There was a woman who often slept across the street; her name was Jackie. I recognized members of the homeless community by name. So, I approached and asked, “Jackie, are you hungry?” Absolutely! Jackie frequently found herself in and out of jail, disappearing for a while before reappearing on the street, talking loudly. I remember you, the guy who gave me food to eat.

You need to be present. I could leave and go home to Elk Grove, but I won’t pretend I’m better than anyone. I learned long ago that you shouldn’t do that to people, especially when you’re being genuine. It was a great place. I had clothes, and there was a guy who needed a coat. “Come here; it’s cold out here. Take this coat.” I brought him a quilted jacket and wasn’t looking for anything in return. That’s it; he needed one. And I hope that someone will give me one if I’m somewhere and need a coat.

I published a book of photography and poetry based on what I saw; some of the titles here are quite unusual.

“There’s a killer amongst us.”

“What happened to soul music?”

“Why is it so easy to direct your anger at me?”

“What have I done to deserve this?”

“You don’t even know me.”

I believe racism is primarily a mental issue because it’s a serious problem to dislike someone or something without truly understanding it. For example, it’s like saying you don’t like chicken without ever tasting it.

Life can be tough. Life on the streets is challenging.

I take photos on the streets of the Oak Park neighborhood in Sacramento. As you can see, I’ve blurred some of the images. I like this technique because it’s not really your business who this person is. I’m just trying to show you. I took a photo of a little boy who was on a field trip. I like that photo. The only Black kid on the trip was on a bus full of little white boys. That made a statement; it stood out to me. Who is this little boy, and what might he say if I had the chance to talk to him about this? I have a grandson who attends a Christian private school. Even though it’s a Christian school, he sometimes faces racism from the other kids.

Today, kids can be so—excuse my language—really fucking mean. Yeah. And it truly affects me, and that’s not good. So, the book titled “Black and Forward, A Street Opera” reflects everything I’m observing: everything happening around me. I wanted to pause the world and reflect. This was my chance. Okay. I couldn’t stop the world, but I could freeze it for a moment. I did that through the pictures and the writing. Don’t call me nigga brother. We’re supposed to come together.

I’m Black, but I am not stuck. Do you understand what I’m saying? I had to find a different way. At what point do I become free?

“I think America needs a mama moment.”

What I’m saying is America needs a fucking spanking. Yeah. Get your shit together. Cause right now, you’re a little raggedy. Yeah. You’re showing your ass. Okay. It’s time to get your shit back together. Stop airing your dirty laundry to everybody around the world. Cut that shit out. You can learn a great deal from the Black community. Joy is one of those things; no one will ever steal that from me.

I don’t care how tough things get or how foolish the world becomes. No one will understand that. It’s my one prized possession that you’ll never touch. I paint because it gives me freedom. I create to experience liberation. All my creativity is a gateway to freedom. I feel like a prisoner of my own making when I’m not creating art.

Frank Sinatra sang, “I got to be me.” And you know he’s also from New Jersey, and I find that statement to be true. Who else can I be? A pale copy of someone else. I would always choose being myself over being a poor imitation of someone else.